1. How Do Lists Really Work?

myList = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for i in myList:

print(i)

Pretty simple and intuitive right? All of us who have learned python have used lists at some point. Almost all tutorials, videos, boot camps and blogs talk about how to use them and what cool methods they provide. But have you ever wondered how do lists really work? How do they resize themselves automatically unlike the static arrays in C? What is Python hiding from us? How does it actually add or remove elements?

That’s exactly what this article is about. We’re going to answer all those questions by looking at the one place that holds the ground truth, the source code. Our mission is to go behind the curtain, peek at the C code that powers Python, and understand what a list really is. No magic, just plain logic.

So, why are we suddenly talking about C? When you type python3 in your terminal, you’re running a program. That program, the most popular implementation of the Python language, is called CPython, and it’s written almost entirely in C.

Think of it as the software that actually runs your Python script. Every time you create a list or call .append(), you’re telling CPython to run a specific C function under the hood. To truly understand how lists work, we have to look at the C code that defines the list.

2. How does Python have Objects?

The first surprising fact is that Python, a famously object-oriented language, is built on top of C, a language that doesn’t have classes or objects in the way we think of them. How does this even make any sense!?

The fundamental building blocks of object-oriented programming are really just structs (to group data), pointers (to create references), function pointers (to represent methods), and indirection (a way to decide which function to run at runtime).

These four building blocks let CPython support the key features of object-oriented programming: keeping data and methods together (Encapsulation), letting one class borrow from another (Inheritance), and letting objects behave differently depending on their type (Polymorphism).

Now we’ll take a look at how those Objects are implemented using C!

Note: For simplicity’s sake we will abstract some of the code, you can still check them out by clicking the hyper links! Since the main branch constantly keeps changing, we stick to 3.11 version.

2.1: The Universal Object – PyObject

This is the root of all Python objects. Every other object struct contains a PyObject within it, making it the absolute base of everything. Below is the definition of PyObject using structs and pointers.

typedef struct _object {

Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt;

PyTypeObject *ob_type;

} PyObject;

Attribute Breakdown

1. ob_refcnt

- Full Name: Object Reference Count.

- What it is: A simple integer counter.

- What it does: It keeps a running score of how many variables or other objects are currently referencing this one.

- Why it matters: This is the main part of Python’s main memory management system. When this count hits zero, Python knows nobody cares about this object anymore and frees its memory.

2. ob_type

- Full Name: Object Type.

- What it is: A pointer to another big, important struct called PyTypeObject.

- What it does: This is the object’s ID card. It tells CPython, “Hey, I’m an integer,” or “Yo, I’m a list.” This PyTypeObject is like a giant lookup table that holds all the “methods” for that type.

- Why it matters: This is the magic that makes polymorphism work. When you call len(my_list), CPython looks at my_list’s ob_type to find the correct C function to run for calculating the length of a list. This helps len() to run not just for lists but tuples, dictionaries and others too.

2.2: The Variable-Sized Foundation – PyVarObject

Some objects, like the number 7, have a fixed size. Others, like lists and strings, are containers that can hold a variable number of things. PyVarObject is the common foundation for all these variable-sized containers.

typedef struct {

PyObject_HEAD

Py_ssize_t ob_size;

} PyVarObject;

That PyObject_HEAD is just a macro, which is a fancy C way of copy-pasting the two fields from PyObject right at the top of this struct. This is basically Inheritance! PyVarObject “inherits” ob_refcnt and ob_type, it then adds one new field which is ob_size.

Attribute Breakdown

ob_size

- Full Name: Object Size.

- What it is: Another integer counter.

- What it does: It stores how many items are currently inside the container.

- Why it matters: This is literally the number that len() returns. It’s a pre-calculated value, which is why calling len() on a list or tuple is instantaneous, O(1), no matter how big it is. No counting required!

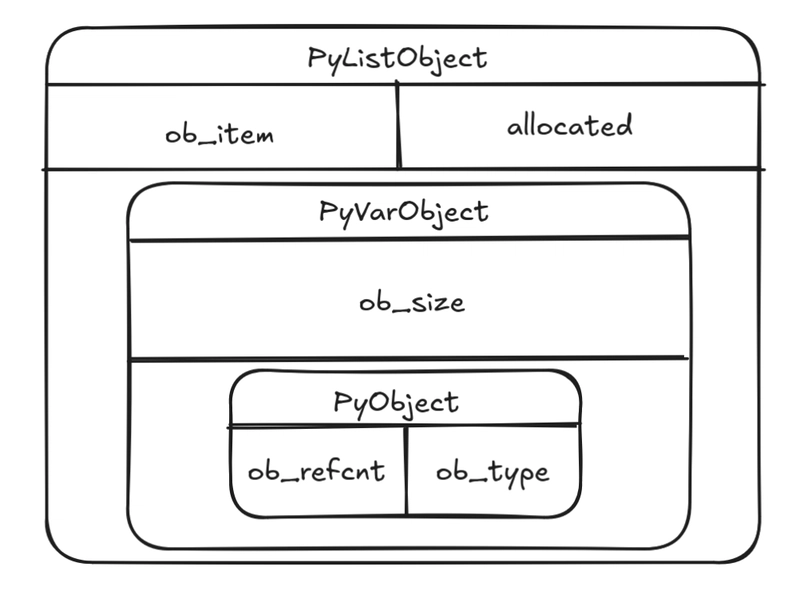

2.3: The List Object – PyListObject

Okay, brace yourself for the big secret, the one that got me into this whole mess. Internally, a dynamic, flexible Python list is basically just a static C array💀. Yeah, I had the same Pikachu face you’re having right now.

typedef struct {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

PyObject **ob_item;

Py_ssize_t allocated;

} PyListObject;

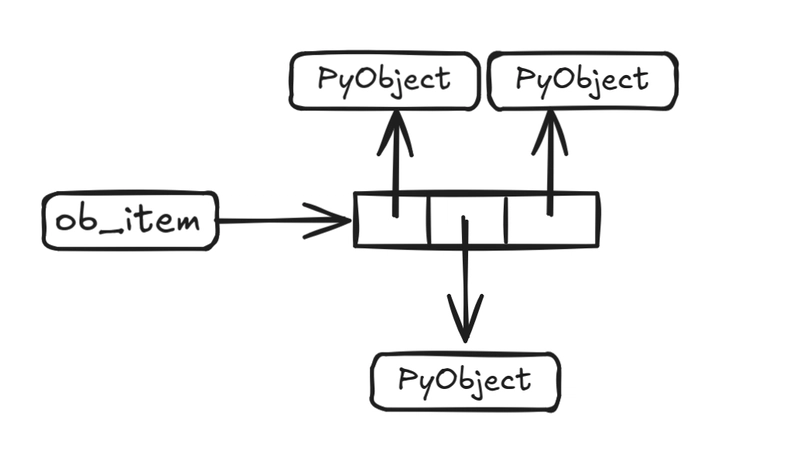

The PyObject_VAR_HEAD macro copy-pastes the fields from PyVarObject (ob_refcnt, ob_type, and ob_size). PyListObject then adds two list-specific fields.

Attribute Breakdown

1. ob_item

- Full Name: Object Items.

- What it is: The star of the show. It’s a PyObject **, which means it’s a pointer to a pointer to a Python object. You can think of it as an “Array of pointers”. And since the pointers are of type PyObject, they can point to any possible Python object.

- What it does: It holds the memory address of a separate, contiguous C array. That array, in turn, holds the memory addresses of all the actual Python objects that are inside the list. It doesn’t hold your ints and strs directly, it holds their addresses.

- Why it matters: This is the “static C array”. Because it’s a contiguous block of memory, getting my_list[500] is a simple calculation, which is why item access is a super-fast O(1) operation.

2. allocated

- Full Name: Allocated Slots.

- What it is: An integer counter and the trusty sidekick to ob_size.

- What it does: It tracks the total number of slots that the ob_item C array has reserved in memory.

- Why it matters: This is the key to how lists seem “dynamic.” Python often allocates more space than it needs right now. This means allocated can be greater than ob_size. The extra, unused slots are waiting patiently for your next .append() call, making it incredibly fast most of the time.

3. A List in Action – The C Functions Behind the Methods

Alright, now that the basics are over, we can finally move to the real functions which power the list methods we all know and love! But first, pat yourself for making this far, you’ve already learned a couple of new things :D

In this section, we’re going to connect the Python methods we use every day to the C functions that do the real heavy lifting. We’ll see how ob_size and allocated change, and witness the famous C array (ob_item) being manipulated directly. First up, the very beginning of a list’s life which is its creation.

3.1: Creation of a List () – PyList_New[] or list()

Every list has a beginning. Its life starts the moment you type my_list = []. This simple command triggers a call to a C function, PyList_New, which acts as the creator for all new list objects.

PyObject *

PyList_New(Py_ssize_t size)

{

PyListObject *op;

// A quick safety check, because a list with -5 items is just silly.

if (size < 0) {// ... internal error handling ...}

// This block only gets compiled if the freelist optimization is enabled.

#if PyList_MAXFREELIST > 0

// Check if a recycled list object is available.

if (get_list_state()->numfree > 0) {// ... C code to grab an object from the freelist recycling bin ...}

else // The recycling bin is empty.

#endif

{

// Create a brand new list object from scratch.

op = PyObject_GC_New(PyListObject, &PyList_Type);

if (op == NULL) {return NULL; // Failed}

}

// If the list is empty, don't allocate the array at all!

if (size <= 0) {op->ob_item = NULL;}

else {

// If a size is given, allocate the C array and zero it out.

op->ob_item = (PyObject **) PyMem_Calloc(size, sizeof(PyObject *));

if (op->ob_item == NULL) {// ... out of memory error handling ...}

}

// Finalize the list's properties.

Py_SET_SIZE(op, size);

op->allocated = size;

_PyObject_GC_TRACK(op); // Tell the Garbage Collector to watch this object.

return (PyObject *) op;

}

Snippet Breakdown

- The Freelist Logic : The first half of the function is a performance hack. CPython keeps a “recycling bin” (the freelist) for recently deleted list objects. Before creating a new list, the code first checks this bin. If it finds an old list object it can reuse, it saves the cost of asking the operating system for new memory, which is a surprisingly slow operation.

PyObject_GC_New: If the recycling bin is empty, this is the fallback. It creates a brand new PyListObject struct from scratch and makes sure the Garbage Collector knows about it.- The Empty List Optimization: The if (size <= 0) block is a clever memory-saving trick. If you create an empty list like [], Python doesn’t even bother allocating the main C array (ob_item). It just sets the pointer to NULL (C’s version of None), saving memory until you actually add the first item.

PyMem_Calloc: If you create a pre-sized list (e.g., [None] * 10), this function is used to allocate the ob_item C array and, importantly, initialize all its slots to NULL.- Finalization: The last few lines set the ob_size and allocated fields (which are the same at birth) and officially register the new object with the garbage collector.

The Takeaway

The creation of a Python list is a highly optimized process. Python’s creators knew that creating many small, empty lists is an extremely common pattern. They implemented the freelist to make creating the list object fast and the empty list optimization to make it memory-efficient by delaying the allocation of the main data array.

3.2: Accessing an Item () – PyList_GetItemmy_list[index]

Now, let’s look at the C code behind the simplest operation: accessing an item by its index, like . This is handled by the function.my_list[i]PyList_GetItem

PyObject *

PyList_GetItem(PyObject *op, Py_ssize_t i)

{

// Is the object actually a list?

if (!PyList_Check(op)) {// ... internal error handling ...}

// Is the index 'i' in bounds?

if (!valid_index(i, Py_SIZE(op))) {PyErr_SetString(PyExc_IndexError, "list index out of range");

return NULL;

}

// It's a simple access from the"static" C array we know :)

return ((PyListObject *)op)->ob_item[i];

}

Snippet Breakdown

PyObject * PyList_GetItem(...): Defines a function that takes a generic object and an index , and returns a pointer to the item found.iif (!valid_index(i, Py_SIZE(op))): This is the bounds check. It makes sure the index is within the valid range (from 0 to – 1) before trying to access it. If not, it sets the error string as .iob_sizeIndexErrorreturn ((PyListObject *)op)->ob_item[i]: This is the main action. It casts the generic object to a specific , then directly accesses the C array at the given index to get the pointer.opPyListObjectob_itemi

The Takeaway

The reason item access is O(1) (constant time) is because this operation is just direct memory math, also known as pointer arithmetic. The computer can calculate the exact memory address of any item using the formula . It jumps directly to the data, which takes the same amount of time whether the list has 10 items or 10 million.start_address + (index * pointer_size)

3.3: What makes the list dynamic? – list_resize

Now for the big one. How does a list magically grow when you append an item? The secret lies in the function. It’s not a method you can call directly from Python, it’s the function that methods like .append() and .insert() call upon when they need to change the list’s capacity.list_resize

static int

list_resize(PyListObject *self, Py_ssize_t newsize)

{

Py_ssize_t allocated = self->allocated;

size_t new_allocated;

PyObject **items;

// The Fast Path: If there's already room, just update the size.

if (allocated >= newsize && newsize >= (allocated >> 1)) {Py_SET_SIZE(self, newsize);

return 0;

}

// The Slow Path: We need more memory.

// Calculate the new, larger capacity.

new_allocated = ((size_t)newsize + (newsize >> 3) + 6) & ~(size_t)3;

// Ask the OS for a bigger C array and copy the old items over.

items = (PyObject **)PyMem_Realloc(self->ob_item, new_allocated * sizeof(PyObject *));

if (items == NULL) {// ... out of memory error handling ...}

// Update the list to use the new array and new capacity.

self->ob_item = items;

Py_SET_SIZE(self, newsize);

self->allocated = new_allocated;

return 0;

}

Snippet Breakdown

if (allocated >= newsize ...): The Fast Path. When a list operation needs to change the size, this first checks if there’s already enough allocated space (for growing) or if the list isn’t too empty (for shrinking). If the new size fits comfortably within the current capacity, it just updates the ob_size and exits.new_allocated = ...: The Growth Formula. If the fast path fails, this line calculates a new, larger capacity. It doesn’t just add one slot; it adds a proportional amount (roughly 1/8th of the new size) to give the list room to grow.items = PyMem_Realloc(...): The Slow Path. This is the expensive part. asks the operating system for a bigger chunk of memory and has to copy all of the old item pointers from the old array over to the new, bigger one.PyMem_Reallocself->ob_item = items; ...: Finally, the function updates the list’s internal pointer and counter to reflect the new, larger C array.ob_itemallocated

\The Takeaway

The efficiency of list growth, especially for .append(), is thanks to this two-path system. Most calls are O(1) because they take the fast path. Occasionally, an expensive O(n) copy happens on the slow path. Python uses a geometric growth formula to ensure these expensive copies happen less and less frequently as the list gets bigger. This spreads the cost of resizing over many appends, making the average cost constant.

3.4 Appending an Item () – list_appendmy_list.append(item)

Now that we’ve seen the working of list_resize, let’s look at how the simple .append() method actually uses it. The journey starts at the C function list_append.

When you call .append(), the first C function to run is list_append. It’s a simple wrapper that handles some paperwork and immediately calls its more interesting helper function, _PyList_AppendTakeRef.

static PyObject *

list_append(PyList_Object *self, PyObject *object)

{

// Py_NewRef increases the object's ref count before passing it on.

if (_PyList_AppendTakeRef(self, Py_NewRef(object)) < 0) {return NULL;}

Py_RETURN_NONE; // This is why append never returns anything.

}

// The real worker function

static inline int

_PyList_AppendTakeRef(PyListObject *self, PyObject *newitem)

{Py_ssize_t len = Py_SIZE(self);

Py_ssize_t allocated = self->allocated;

// The Fast Path: Is there an empty slot at the end?

if (allocated > len) {

// Yes! Just drop the item in and update the size.

PyList_SET_ITEM(self, len, newitem);

Py_SET_SIZE(self, len + 1);

return 0; // Success!

}

// The Slow Path: No room! Call for backup.

return _PyList_AppendTakeRefListResize(self, newitem);

}

The Takeaway

The .append() method is designed for one thing: speed. It always tries to do the cheapest possible O(1) operation first. It calls the function to expand only in the case when it’s absolutely necessary. This “check-first” logic is what makes appending to a list so efficient in the vast majority of cases.list_resize

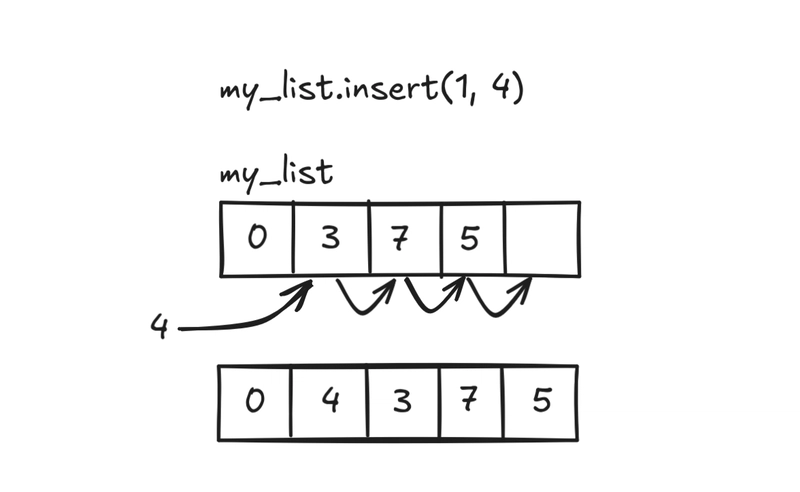

3.5: Inserting an Item () – ins1my_list.insert(index, item)

Appending is fast because we’re just adding to empty space at the end of the list. Inserting an item at the beginning or in the middle of a list can be slow. The C function shows us the reason.ins1

static int

ins1(PyListObject *self, Py_ssize_t where, PyObject *v)

{Py_ssize_t i, n = Py_SIZE(self);

PyObject **items;

// First, make sure there's at least one empty slot.

if (list_resize(self, n + 1) < 0)

return -1;

// The Memory Shuffle! Pick the last element and move it one step forward

// keep doing it till our required index has an empty slot.

items = self->ob_item;

for (i = n; --i >= where;)

items[i+1] = items[i];

// Place the new item in the now-empty slot.

Py_INCREF(v);

items[where] = v;

return 0;

}

The Takeaway

Insertion is an O(n) operation because of that for loop. To insert an item at the beginning (), the loop has to touch and move every single element in the list to make room. The amount of work is directly proportional to the size of the list, hence O(n).where=0

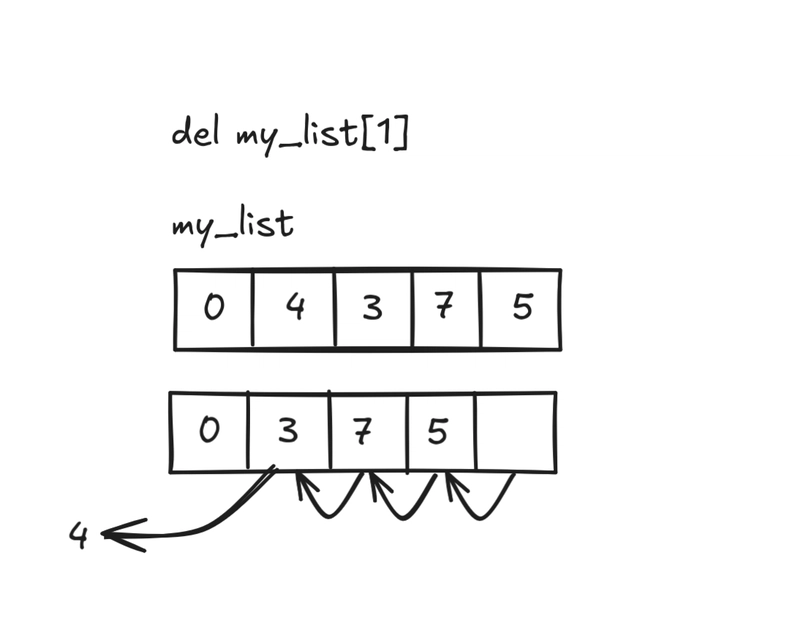

3.6: Deleting an Item () – list_ass_slicedel

Deleting an item is the reverse problem: instead of making space, we have to “close the gap.” This logic is found inside the function, which uses a C standard library function called .list_ass_slicememmove

Note: The actual C function that handles this, , is quite complex because it’s built to handle all kinds of slice operations. The function shown here is a simplified version I’ve created that focuses on the core logic for deleting a single item.

list_ass_slicedelete_one_item

static int

delete_one_item(PyListObject *self, Py_ssize_t i)

{Py_ssize_t n = Py_SIZE(self);

PyObject **items = self->ob_item;

Py_ssize_t items_to_move = n - i - 1;

// ... Decrement reference count of the object being deleted ...

// The Main Event: close the gap.

if (items_to_move > 0) {memmove(&items[i], &items[i+1], items_to_move * sizeof(PyObject *));

}

// Finally, shrink the list's size by 1.

return list_resize(self, n - 1);

}

Snippet Breakdown

items_to_move = n - i - 1;: Calculates how many items are to the right of the item we’re deleting. These are the items that need to be shifted.memmove(&items[i], &items[i+1], ...): This is the Main Event. is a highly optimized C function that physically moves a whole block of memory from one location to another.memmove&items[i]: The destination address (the slot we’re closing up).&items[i+1]: The source address (the slot right after the deleted one).- This command effectively takes all items to the right of the deleted one and slides them one spot to the left.

The Takeaway

Deletion is an O(n) operation because of . To “close the gap” left by a deleted item, CPython must physically move all the elements that came after it. If you delete the first item (), it has to move the entire rest of the array ( items). The work is directly proportional to how many items you have to move.memmovedel my_list[0]n-1

4. The Final Takeaway: What a List Really Is

So, what was Python hiding from us? After peeling back the layers and staring into the C source code, we found the answer, and it isn’t magic. The dynamic, ever-growing list we use every day is built on top of a simple, static C array. That’s the secret.

Knowing this changes how you see your own code. That fast access with my_list[99999]? That’s the raw power of a C array doing a simple math problem to find a memory address. But that power has a price. The reason my_list.insert(0, ‘x’) can feel so slow is that you’re witnessing the brute-force reality of that same C array, as it physically shuffles every single element one by one just to make room at the front.

In the end, the list is just a beautiful piece of engineering built on a clever trade-off. It bets that you’ll append more often than you’ll insert at the beginning, so it optimizes for that case with its over-allocation strategy. And now, you’re in on the secret.

Congratulations on making it to the end! 🥳🎉

If you have any questions, suggestions or other topics to recommend, feel free to reach out!

Thank you so much for reading, it means a lot to me! :)

FAQ

1. Why can Python lists resize automatically, but C arrays cannot?

Although Python lists are underlain by static C arrays (stored in the ob_item field of PyListObject), they achieve “dynamic resizing” through the list_resize() function. When the number of list elements (ob_size) approaches or exceeds the allocated slots (allocated), list_resize() applies for a larger memory space using a “geometric growth formula” (approximately 1/8 of the current size + 6), copies elements from the old array to the new space, and then updates the ob_item pointer and allocated value. In contrast, the size of a C array is fixed when defined and cannot be modified directly—manual memory application, data copying, and pointer updates are required, so it lacks the “automatic resizing” capability.

2. Why does len(my_list) return instantly regardless of the list size?

The return value of the len() function is directly fetched from the ob_size field of PyListObject. This field is updated in real time when elements are added to or removed from the list (e.g., ob_size + 1 for append(), ob_size - 1 for del), making it a “precomputed value”. There is no need to traverse the list for counting, so the time complexity is O(1), and the result is returned instantly whether the list contains 10 or 10 million elements.

3. Why is my_list.append(item) efficient, while my_list.insert(0, item) is inefficient?

append()prioritizes the “fast path” by default: ifallocated > ob_size(free slots exist), it directly places the element at the end of the list and only updatesob_size, with a time complexity of O(1). Even if resizing is needed (taking the “slow path”), the “geometric growth” strategy reduces the frequency of resizing as the list grows, keeping the average efficiency close to O(1).insert(0, item)first requires callinglist_resize()for resizing (if no free slots are available), then shifts all elements one position backward via aforloop (to free up the first slot), and finally inserts the new element. The workload of shifting elements is proportional to the list size, resulting in a time complexity of O(n), which makes it much less efficient thanappend().

4. Will memory be released immediately after deleting an element from a list?

No, it will not be “immediately released” completely, and there are two scenarios:

- For the deleted element: its reference count is decremented by 1. If the count drops to 0, Python’s Garbage Collector (GC) will release the element’s memory at a later time.

- For the list’s own memory: after deleting an element,

list_resize()checks if “shrinking” is needed (only when the newob_sizeis less than half ofallocated). If shrinking occurs, some free memory is released, but shrinking does not happen after every deletion to avoid the overhead of frequent memory application/release. Additionally, CPython stores deleted empty list objects in a “freelist” for reuse when creating new lists later, further optimizing memory efficiency.

5. Do Python lists store data directly or store pointers?

Python lists do not store data directly; instead, they store “pointers to Python objects”. The ob_item field of PyListObject is of type PyObject ** (pointer to a pointer), which points to an “array of pointers”—each element in the array is a pointer to a specific Python object (e.g., integer, string, dictionary). This design allows lists to hold elements of different types (all objects inherit from PyObject) and avoids direct data copying (only pointers are manipulated), improving operation efficiency.